What Happens if Coke Continues to Lose in Tax Court?

Coca-cola recently lost an appeal of a transfer pricing court case, which concluded that Coke owes an additional $3.1 billion in tax for 2007 through 2009.¹ In addition to denying the Motion for Reconsideration on procedural grounds, Tax Court Judge Albert Lauber decided to elaborate on why Coke’s positions for overturning the decision were “futile.”²

Coca-Cola has disclosed a tax reserve of $400 million in its 2021 annual report. However, the annual report also includes an estimate of $13 billion if the IRS ultimately prevails. Coke currently has $10.9 billion in cash and short-term investments as of December 31, 2021.³

While the company expects to win on appeal, Judge Lauber concluded that “[H]ope is not something that gives rise to legal or constitutional entitlements.”

Coca-Cola may actually owe $13 billion to the IRS, and multinationals can draw several lessons from this case – here’s why

Why Is Coca-Cola in Tax Court?

In 1996, Coca-Cola settled a 1987 to 1995 transfer pricing audit with the IRS, reaching an agreement on a profit split formula between companies to resolve issues. Although the IRS did not raise transfer pricing as an issue over several audit cycles, the IRS did issue transfer pricing adjustments for 2007 to 2009, designating the case for litigation in 2015.

The IRS concluded that Coke was significantly undercharging subsidiaries in Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Ireland, Mexico, and Swaziland over several years. In effect, the IRS argued that Coke-US was not receiving proper compensation from subsidiaries utilizing intellectual property developed by the Atlanta, Georgia-based company.

Coca-Cola attacked the IRS’ adjustments on multiple fronts, engaging economists, constitutional scholars, and industry experts to justify subsidiary profits and why the IRS had no standing to audit. Even after losing the Tax Court Case, Coca-Cola reiterated several arguments in their more recent pleadings:

- Coke’s subsidiaries had significant risks in marketing Coke products in their respective regions and therefore should have earned higher profits.

- Coke is using the same pricing system as agreed to settle the 1996 audit.

- For the 1996 closing agreement, the IRS agreed not to assess transfer pricing penalties if they continued with the same transfer pricing system.

- Legally, Coke should be able to rely on the 1996 settlement since the IRS had not challenged transfer pricing for five audit cycles.

What Did the Judge Decide?

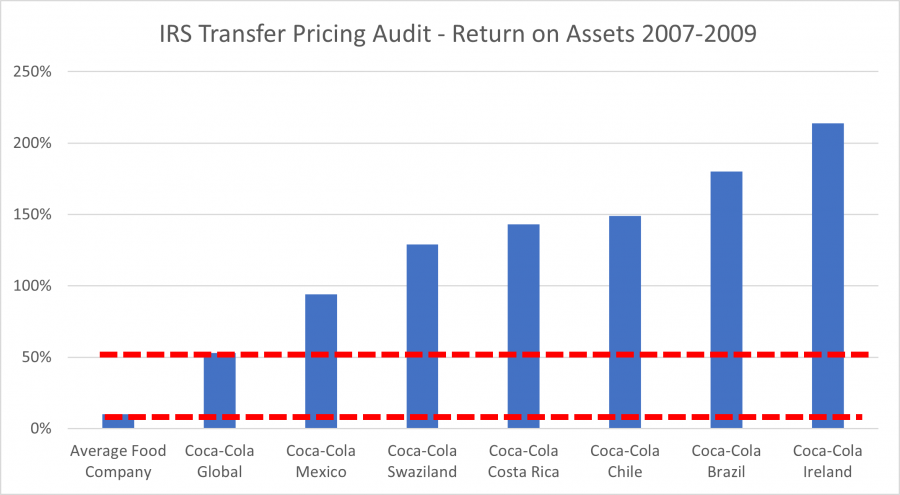

From the court case, Judge Lauber was persuaded by the IRS’ approach of comparing each Coca-Cola subsidiary’s excess profits against independent bottlers. What could be considered “excess” can be a difficult economic question, but the following graph places Coca-Cola subsidiary profits on a return-on-assets basis in perspective:

Reading left-to-right, “Average Food Company” represents the average return on assets earned by food and beverage companies from 2007 to 2009. Coca-Cola, at 53%, represents the return on assets earned by the global Coca-Cola company. From the IRS perspective, Coke’s subsidiaries in Mexico (94%), Swaziland (129%), Costa Rica (143%), Chile (149%), Brazil (180%), and Ireland (214%) earned far too much profit overseas – thereby underpaying US tax.

Beyond the profit margin comparison, Judge Lauber summarily dismissed Coca-Cola’s position that the company could rely on an old closing agreement and lack of audit activity. The Judge noted that Coca-Cola could have negotiated an Advance Pricing Agreement (“APA”) if they wanted transfer pricing certainty. Finally, Coca-Cola’s Motion for Reconsideration was filed well after a 30-day deadline under Tax Court Rules of Practice and Procedure.

What Does This Court Case and Denial Imply for Taxpayers?

The Coke transfer pricing audit approach involves comparing subsidiary profit margins against ‘comparable’ companies in similar markets. More specifically, the IRS applied the “Comparable Profits Method” (“CPM”), a specified method under US transfer pricing regulations.

In practice, US multinationals that have highly profitable international subsidiaries face increased risks of an audit. If the multinational’s subsidiaries are greater than the range of profit margins earned by the benchmarks, the IRS can make tax adjustments. In our experience, benchmarks for these profit margins will vary by industry, but reviewing each subsidiary’s profits as a percentage of operating assets is an ideal place to start.

The Judge also dismissed Coca-Cola’s argument that a lack of audit activity or a prior settlement provided any certainty over transfer pricing. In effect, taxpayers should not have a false sense of security because transfer pricing has not been recently raised as an audit issue.

KBKG Insight:

Coca-Cola contends they will prevail upon appeal and that their tax reserve is reasonable. The IRS is confident in its position, and we expect auditors to rely upon this Coca-Cola court case win in audits going forward.

Do you or your client have concerns about transfer pricing? KBKG’s Principal and Practice leader, Alex Martin, is here to assist. Alex delivers 20-plus years of practically-focused transfer pricing expertise to clients and advisors. KBKG was named one of the World’s Leading Transfer Pricing Advisory Firms for 2021-2022 by International Tax Review. » Schedule a call now

KBKG also has many resources on our website to help you answer any other questions not listed here.

» Learn about Transfer Pricing

Sources

- Coca-Cola Co. et al v. Commissioner, T.C. Docket 31183-15, Served October 26, 2021. https://www.taxnotes.com/research/federal/court-documents/court-opinions-and-orders/tax-court-won%E2%80%99t-allow-coca-cola-to-file-out-of-time/7cngr?h=*

- Coca-Cola Company and Subsidiaries v. Commissioner, Docket No. 31183-15, Entry #747 and #748 and Order in response to Motion for Leave and Motion for Reconsideration

- https://investors.coca-colacompany.com/filings-reports/annual-filings-10-k

This article was originally published on 3/22/2022 and updated on 12/9/2023

About the Author

Alex Martin – Principal

Alex Martin – Principal

Midwest

Alex Martin is Principal and Transfer Pricing Practice leader at KBKG, operating from Michigan. He has 24 years of full-time transfer pricing experience working in Washington, D.C.; Melbourne, Australia; and Detroit, Michigan over the course of his career. KBKG was named one of the world’s leading transfer pricing consultancies by the International Tax Review for 2021-2022. » Full Bio